Trump Takes to Twitter as Puerto Rico's Crisis Mounts

The president offered a fusillade of tweets—attacking critical press coverage and local officials pleading for help—as the response on the island continued to fall short of the need.

Grant the president this: Whatever shortcomings he might have as a national uniter, or soother of emotions, or chooser of Cabinet secretaries, he possesses a practically unerring ability to make anything about himself.

As the humanitarian crisis in Puerto Rico continues, Donald Trump has spent the weekend using his favorite medium, his Twitter account, not to soothe emotions or offer succor to the people of the island but to pick an increasingly acrimonious fight with the mayor of San Juan, its largest city, and to tell Puerto Ricans that the lack of water, food, and electricity they are experiencing is not reality but a fabrication by the news media. Saturday morning, my colleague James Fallows called Trump’s attacks on Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz “a new low,” but Trump has managed to dig deeper since.

It started here:

The Mayor of San Juan, who was very complimentary only a few days ago, has now been told by the Democrats that you must be nasty to Trump.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 30, 2017

...Such poor leadership ability by the Mayor of San Juan, and others in Puerto Rico, who are not able to get their workers to help. They....

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 30, 2017

...want everything to be done for them when it should be a community effort. 10,000 Federal workers now on Island doing a fantastic job.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 30, 2017

Over an unusually prolific series of tweets (some of which are not duplicated here, but can be seen on his feed), he went on to attack the press:

Fake News CNN and NBC are going out of their way to disparage our great First Responders as a way to "get Trump." Not fair to FR or effort!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 30, 2017

In what has become distressingly commonplace, he accused the press of sedition and undermining the military:

The Fake News Networks are working overtime in Puerto Rico doing their best to take the spirit away from our soldiers and first R's. Shame!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 30, 2017

Later in the day he was at it again:

Results of recovery efforts will speak much louder than complaints by San Juan Mayor. Doing everything we can to help great people of PR!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 30, 2017

By Saturday morning, he was calling any critic an "ingrate":

We have done a great job with the almost impossible situation in Puerto Rico. Outside of the Fake News or politically motivated ingrates,...

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 1, 2017

(In the midst of this, he again found time to scold NFL players who protest during the National Anthem and to demand credit for raising the numbers of his chosen candidate in the Alabama GOP Senate primary, even though the candidate lost. A participation trophy for the president, please!)

Any ordinary leader, faced with a crisis of this magnitude, seeks to project sympathy for victims, promising to get aid to them as fast as possible. Trump is no normal leader. For days after the crisis, as I wrote on Friday, the president loudly proclaimed (against the evidence) that the response is going swimmingly. But as the remaining unmet needs in Puerto Rico become clearer, and after Cruz criticized Acting Secretary of Homeland Security Elaine Duke for calling Puerto Rico “a good news story,” Trump has taken any complaints about the federal response as personal attacks. He also referred to those executing the federal response as “my people.” Like Louis XIV, the president adores ostentation and proclaims, “L’etat, c’est moi.”

Within Trump’s worldview, this makes sense: If the alleged success of the relief effort a few days ago reflected Trump’s personal brilliance, then any criticism of the effort must represent a personal attack on the president. Outside of Trump’s worldview, however, this is not only illogical but inhumane: As American citizens in an American territory remain without basic necessities, the president of the United States seems primarily concerned about settling political scores and making it about him.

Retired Lieutenant General Russel Honoré, who won applause for turning around the chaotic Katrina relief effort 12 years ago, put Trump’s attacks on the San Juan mayor in clear contrast during a CNN interview Saturday.

“The mayor's living on a cot, and I hope the president has a good day at golf,” Honoré said, alluding to Trump’s weekend at his luxurious Bedminster Club in New Jersey.

Trump’s response this weekend is shocking (not to say surprising, as Fallows noted last weekend during a prior chapter in this crisis) not just because he is attacking public officials desperate to get aid for their people, but because his denunciation of press coverage verges on fantasy. Not for the first time, Trump seeks to deny the plain truth of news reports, but in this case there is no shortage of visual evidence to confirm the destruction. Even if he thinks he can fool mainlanders, Trump is also demanding that Puerto Ricans believe him, rather than their lying eyes:

To the people of Puerto Rico:

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 30, 2017

Do not believe the #FakeNews!#PRStrong🇵🇷

It’s hard to imagine this would convince a Puerto Rican whose house was destroyed, was going without medicine, or had no reliable drinking water. But since the country’s electrical grid is down and cellphone towers are destroyed, relatively few of them are likely to see the tweet anyway.

Anyone who does see his tweets, though, should treat them dubiously. Trump claimed Sunday morning that “all buildings [are] now inspected,” but Governor Ricardo Rosselló said he was unaware of any such inspections. Last week, as Trump said Puerto Ricans had plenty of water, Rosselló said only 40 percent of the population had reliable drinking water.

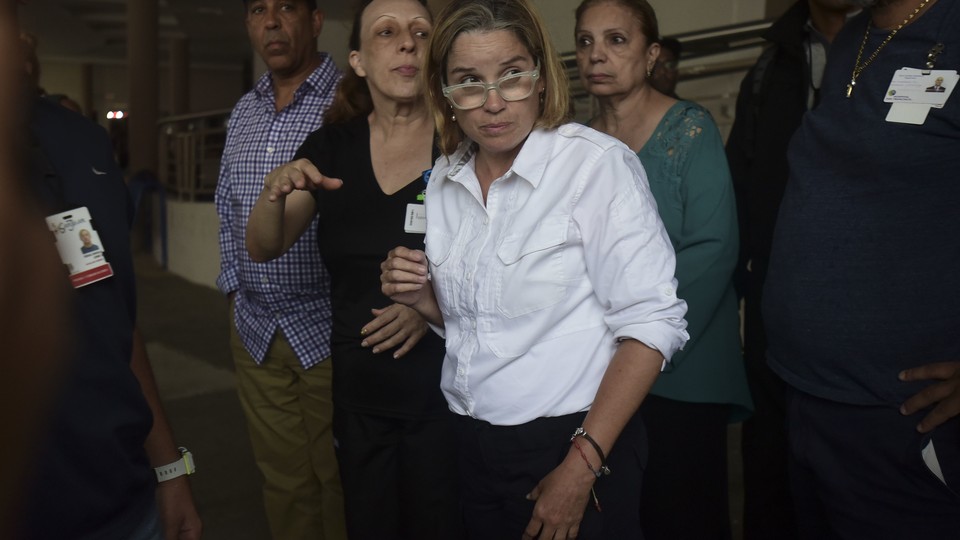

Trump’s attacks on Cruz are a turn in their relationship. On Tuesday, Trump tweeted to thank her for praising him. (His focus on who is praising him, as much or more than what is being done, underscores his unusual priorities.) But on Friday, after Duke called the relief effort “a good news story,” Cruz lost her patience during a live CNN interview.

“Dammit, this is not a good news story!” she said. “This is a people-are-dying story. This is a life-or-death story. This is a there’s-a-truckload-of-stuff-that-cannot-be-taken-to-people story. This a story of a devastation that continues to worsen because people are not getting food and water.”

Even though the mayor had not mentioned Trump’s name, he took her remarks as a personal attack, and has spent much of the last 48 hours strafing her on Twitter. I wrote on Friday that Trump’s repeated mentions that Rosselló had thanked him constituted a form of blackmail—a reminder that should Rosselló’s praise cool, Trump could always turn the power of the state from aid into enemy. The president’s turn on Cruz proves that.

The weekend fusillade recenters two tendencies about Trump’s handling of crises. One is that he personalizes everything and makes it about himself, whether that’s a manmade crisis like the white-supremacist march in Charlottesville or an environmental one like Hurricane Maria. Another is his haste to assign blame elsewhere. North Korea? Previous administrations failed to deal with it. (True, though Trump has escalated tensions.) Gas attacks in Syria? Obama’s fault. Iraq and Afghanistan? Impossible problems. (Never mind that Trump had promised, “I alone can fix it.”) And now Puerto Rico? An “almost impossible situation.”

Trump is not wrong that there are immense challenges posed by the Puerto Rican response: Maria was the third major hurricane to strike the U.S. in a month, and the second to hit Puerto Rico. Getting aid to an island so far off the mainland, and repairing the damage, is difficult. But one can make the worst of a bad situation or the best, and the government is leaning toward the latter. He made the situation worse by saying everything was fine when it clearly wasn’t, thus inviting more scrutiny; another part is inexplicably attacking the victims of the crisis as they try to bounce back.

Trump is not the only federal official to bridle at Cruz’s remarks. On Fox News Sunday, FEMA Administrator Brock Long did not personally attack the mayor, but he did suggest she was not playing well with federal workers.

“If mayors decide not to be a part of that, then the response is fragmented. And the bottom line is, is that we’re pushing everybody, we’re trying to push her, in there,” Long said. “You know, we can choose to look at what the mayor spouts off or what other people spout off, but we can also choose to see what’s actually being done, and that’s what I would ask.”

There are growing questions, however, about the president’s material handling of the effort, too. One reason the president is so furious at the press is surely a damning Washington Post story published Friday night that depicted Trump as disengaged and unaware. Though he spoke with Duke briefly about his travel ban the previous Friday, he was not in touch with her again until Tuesday. Instead, Trump spent the weekend playing golf and jousting with professional athletes via social media. Only later did he come to understand the scale of the disaster, when he saw it on TV. As usual, it was personal criticism that really pricked Trump’s attention:

The sense of urgency didn’t begin to penetrate the White House until Monday, when images of the utter destruction and desperation—and criticism of the administration’s response—began to appear on television, one senior administration official said.

A common refrain through the serial crises first eight months of the presidency has been to wonder what would happen when Trump encountered a genuine crisis that was neither political nor of his own making. His first tests, with Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, went relatively smoothly. Maria does not look so promising. Trump’s impulse to personalize every incident and make it about him is jarring, but in one way, he is right: If the public deems the response to Maria a failure, no number of combative or self-exculpatory tweets will prevent him personally from receiving the blame.